Another Theory on Why Electoral College Bias Is Declining

In addition to other widely noted factors, Harris is running best in competitive states where housing costs are a relatively minor concern.

Dear readers,

In conjunction with today’s final national New York Times-Siena poll, which finds Donald Trump and Kamala Harris tied at 48% each, Times pollster Nate Cohn has written another1 article about the likelihood that the electoral college bias against Democrats that was a key feature of the 2016 and 2020 elections has significantly decreased, possibly all the way to zero.2 Cohn writes:

In our national surveys, Mr. Trump makes huge gains in the places where Republicans excelled in the midterms; he makes no gains at all where Republicans struggled, which includes states like Pennsylvania.

Remember, in 2020, Joe Biden won the national popular vote by 4 points, but he won the tipping point state of Wisconsin by less than a point, and Pennsylvania by just over a point. The fact that Biden (and Clinton) ran worse than they did nationally in those key swing states led to a widespread assumption that Harris must win the popular vote by several points in order to actually win the election. But the Times-Siena poll has been finding big shifts that counter that theory: when it simultaneously polled Pennsylvania and the country last month, Times-Siena found Harris running very slightly better there than nationally. Meanwhile, Times-Siena has found Harris running much worse than Biden did four years ago in states that are not competitive, including a poll that found her trailing by an eye-popping 13 points in Florida.

In other words, the Times-Siena polling suggests that Trump has been making gains compared to four years ago, but those gains are very electorally inefficient: his inroads with younger minority voters are helping him run up the score in Florida and lose by less in New York, and are likely to help him reclaim Sun Belt states like Georgia and Arizona, but the Times-Siena polls don’t show him making the gains he needs in disproportionately white Rust Belt states in order to get to 270 electoral votes. In fact, Harris may be running slightly better than Biden did with white voters four years ago.

Times-Siena stands out from other pollsters in reaching this geographic finding, and Cohn has written some fairly technical pieces about a likely reason why: unlike many pollsters, Times-Siena does not weight its poll results on recalled vote. Other pollsters have started doing this, ensuring that if Biden won Pennsylvania by one point four years ago, the new poll sample includes voters who say they voted for Biden last time by a margin of one point. There are arguments for and against this approach, but one of Cohn’s main arguments for not doing it is that it can cause you to miss shifts in the electorate: for example, if lots of disproportionately Republican voters moved into Florida since the 2020 election, a weighted poll may miss that phenomenon and understate Trump’s strength there. On the other hand, because respondents have historically been excessively likely to recall voting for the election winner last time around, weighting on vote recall can systematically bias polls against the incumbent party. That means weighted polls in a state like Pennsylvania could be applying a penalty to Harris’s total that wouldn’t show up in the election results.

In today’s newsletter, Cohn even raises the possibility that Harris could narrowly lose the popular vote and still win the electoral college.

One of the best arguments against this thesis is history: On average, the coalitions in the last election tend to be like the ones in the next election, and that should especially be the case since Trump is on the ballot again (and of course, until July so was Biden). But there are also some reasons to believe this election could bring the sort of major relative shifts in performance across regions that the Times-Siena polling implies, even if the shifts aren’t large enough to wipe out the bias entirely.

Here are three circulating arguments that support the case for the shift:

It happened in 2022. As Cohn notes, the Times-Siena poll results track the actual midterm election results two years ago, when Democrats lost major ground in Florida, the New York metro area and Southern California, while performing quite well in the Rust Belt.

Racial depolarization should change the electoral map to Democrats’ advantage. Times-Siena is far from the only pollster finding that Harris’s deterioration is concentrated among non-white voters, and that she may even be making slight inroads with white voters. A whiter coalition tends to be electorally advantageous because non-white voters live disproportionately in the four largest states (California, Texas, Florida and New York), all of which are non-competitive.

Abortion helps Democrats in the right places. A lot has been written about non-white voters (especially but not exclusively men) who voted Democratic in the past but are drawn to Trump because they are frustrated about the cost of living and feel the economy was better when he was president. Here, for example, is a very interesting Times piece on political divisions within Hispanic families in Arizona. But there’s less focus on the voter who might have backed Trump four years ago but would vote for Harris today. Who you should be imagining is a white woman who didn’t go to college, isn’t especially religious, and is more focused on her support for abortion rights after the Dobbs decision. Non-college-educated white voters live disproportionately in the Rust Belt swing states, and abortion may be more politically salient there than elsewhere because abortion access can actually depend on the right electoral outcome.

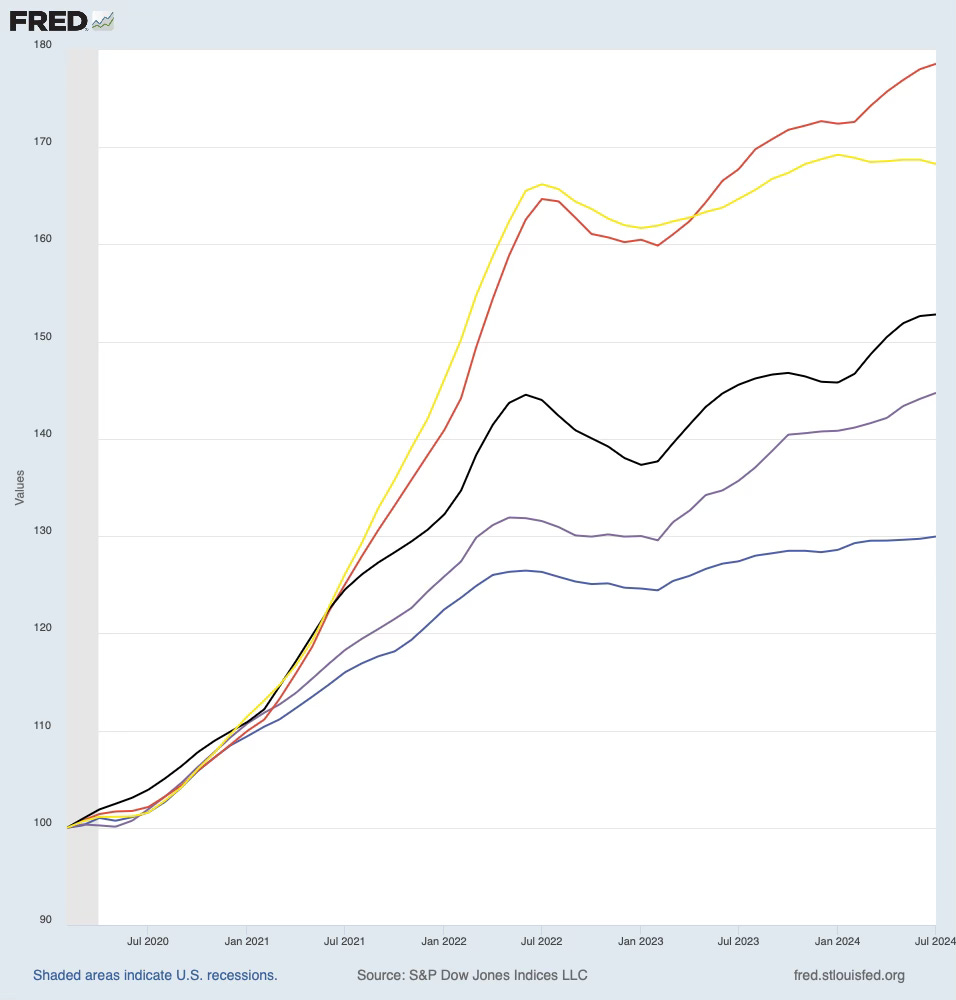

I want to raise one additional theory of why the electoral map would be changing to Democrats’ advantage: housing costs. Home prices zoomed upward when the pandemic hit; since 2022, they have stabilized, but higher interest rates have driven up the effective cost to own a home of a given price. This is a major political issue, and one that cuts differently across regions and demographics. One thing about the young minority voters among whom Republicans are making gains is that they are a relatively house-poor demographic, more likely to be renting or trying to buy a home, and therefore highly exposed to house price increases. Older and whiter voters are more likely to own their own homes, and so the rise in house prices isn’t necessarily affecting their cost of living — in fact, they might be experiencing it mostly as an increase in wealth.

When we look at the electoral bloodbath that Democrats faced in New York and Florida two years ago, and also their underperformance in California, one thing I see is that these are all places where housing is really expensive. Florida, in particular, has experienced much higher housing cost growth since COVID than the country as a whole. It’s no surprise that voter discontent about cost of living would be especially acute in these areas. Meanwhile, metropolitan areas in the Midwest have experienced relatively modest housing price growth, and that growth has been off a lower base — a 10% increase in rent is much more affordable if your rent starts out as 15% of your income than if it starts as 30% of your income. So it makes sense that Democrats’ worst issue — cost of living — would be biting less hard in the Rust Belt than elsewhere.

These demographic and regional effects also interact with each other: the Midwest metro areas where housing costs have been relatively less of a problem are also relatively white, while many of the most housing cost-pressured metros in the US are highly diverse.

In fact, looking at the 2022 election results, I’d say the housing costs theory fits the data better than one I see a lot more often: that Democrats’ regional underperformance was a reaction against left-wing blue-state governance run amok. No, I don’t think voters on Long Island are happy about the way Democrats are managing crime and homelessness in New York City. But Chicago and Minneapolis have also been poster children for “crazy liberal disorder,” and there was no similar electoral backlash against Democrats in their suburbs two years ago.3 Plus, it is hard to separate public discontent about street homelessness from public discontent about the high cost of housing because they have the same root cause and will tend to show up in the same places. And the Republican surge in Florida — where house prices soared and cities were not generally perceived as festering dens of disorder — also fits my theory better than the dominant one.4

All of this is not to say that I expect Kamala Harris to lose the popular vote but eke out a 270-electoral vote win by holding onto Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin plus one electoral vote from Omaha, riding on her strength with voters who aren’t that aggrieved about the price of housing. My gut feeling, since we’re apparently doing this, is that if the election were held today, she would fall slightly short. The scenario that actually haunts me is one where she barely holds on in Pennsylvania but loses Wisconsin, which produced Biden’s narrowest Rust Belt win four years ago. But I do believe that, whoever wins the election, we will see that the Electoral College has moved much closer to unbiased than it was in the last two elections.

Very seriously,

Josh

He also wrote on this last month; it seems the Times-Siena polling data that came in since then has continued to support the thesis.

In fact, Cohn floats the possibility that the bias has fallen below zero — that Harris could lose the popular vote and win the Electoral College. Neither Cohn nor I would call this anything close to a base case, and other analysts are skeptical. Nate Silver’s election model, for example, still holds that the odds of Harris winning the electoral college while losing the popular vote are less than 1%. But Silver’s model does show that the bias is expected to be lower than in 2020, and he wrote today that he’s open to the possibility that Times-Siena is on to something that other pollsters are not, in which case such an outcome must “be at least a little bit more likely than our model assumes.”

According to an analysis from SplitTicket, the congressional generic vote swung against Democrats from 2020 to 2022 by nearly 4 points nationally. There was wide variation across states: the swing was 14 points in New York, 12 points in Florida, and 6 points in California, but just 2 points in Illinois and 0 in Minnesota. In Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania, there was actually a modest swing toward Democrats.

I’d also note that there’s an interaction between the politics of housing costs and immigration. Nate Silver writes today that even in multicultural Canada, politics have shifted in a strongly anti-immigrant direction that has driven Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to announce sharp new curbs on migration. Well, one key political fact about Canada is that their housing market is even more insane than ours, with higher ratios of home prices to incomes, and especially eye-watering prices in the diverse metros of Toronto and Vancouver. One of the key arguments JD Vance has been making against immigration is that migrants drive up demand for homes and therefore house prices and rents. I agree with Silver that Democrats are facing a significant electoral penalty for their failure to control migration during Biden’s term, but it would make a lot of sense to me that this penalty would be most acute in the places where housing costs are high and rising quickly, causing more voters to believe they are facing a personal economic penalty due to high immigration.

Josh you’re an even keel analyst. What is your alarm level about a second Trump term? I try to stay grounded but I’m worried we’ll break something in an irrevocable way.

I hope you’re right. At this point, hopium is a powerful drug.