Democrats Are Paying For Their 2021 Mistakes

In Biden's first 100 days, he created inflation trouble for himself that he can't easily fix now. The challenge for Democrats will be to climb out of this situation by 2024.

Dear readers,

Matt Yglesias wrote last week to “pre-register” his take on the midterm elections. He thinks Democrats are going to underperform their polls once again, and he argues the polls themselves are a huge problem — that by persistently overstating Democratic support levels, polls have lulled the party into taking unsustainably unpopular positions, which they falsely believe won’t cost them elections, because the polls say they’re doing fine.

He complains in particular about two recent overreaches: student debt relief, which he says has undermined Democrats’ message about fighting inflation; and an insistence on taking left-of-Roe stances on abortion (even in swing states), which has harmed Democrats’ efforts to draw a favorable contrast on abortion rights.

I agree with Matt that these two choices are mistakes, but I don’t think these mistakes provide the core account of what’s gone wrong in the last few weeks for the party. Democrats’ biggest political mistake that’s hurting them this fall is one Matt mentions very briefly, and it’s a mistake Democrats made in 2021, and not really in 2022. Matt writes:

Given that everyone agrees gasoline prices are politically significant, how much effort did Nancy Pelosi, Chuck Schumer, and Joe Biden put into thinking about how to spur an oil production recovery back when they were planning the transition?

This gets at the extreme difficulty of Democrats’ political position right now: They are being punished less for extreme positions they’re taking now than for policy mistakes they made in the first half of 2021 — really, in the first few months of the Biden administration. Those policy mistakes have caused inflation to be more elevated than it otherwise would be, and gasoline prices specifically to be more elevated than they otherwise would be. Better messaging, or even better current policy positioning, wouldn’t do a lot to reduce the political penalty associated with those high prices. The key is to make prices lower, but it’s not possible to go back and un-make the mistakes that fueled the price hikes in the first place:

Biden entered office pursuing a fossil fuel agenda animated by the idea that additional North American production should be discouraged. He canceled the Keystone XL pipeline, and he essentially paused the leasing of federal lands for oil and gas production. The theory behind this agenda was coherent — restricting the supply of fossil fuels would push consumers toward renewable energy and accelerate the green transition — but that’s a strategy that inherently involves pushing prices up. High prices are the mechanism that would cause consumers to transition. An idea that liberals now treat as obvious — that voters mostly just care about keeping energy prices low — does not seem to have influenced Democrats’ ideas about what energy policies are politically reckless until a few months ago. Obviously, the war in Ukraine and its effects on global energy prices made domestic energy abundance a more urgent political issue than one might have foreseen, but I’ll get to that — better policy in 2021 would have meant an administration more prepared for what happened in 2022.

Biden overstimulated the US economy with a much-too-large final round of COVID relief. Democrats ensured that households and state governments had more cash to spend in this economy than its productive capacity could handle, and that caused inflation to spike, which is the number one reason voters are mad at Democrats today. But most of that money already went out the door last year, and even if Democrats were more disciplined this year about fiscal expansion — if Biden had followed Matt’s and my preferences and refused to do student debt relief, for example — it wouldn’t have affected inflation that much right now. The best thing would be a time machine so they could go back and cut a trillion dollars out of the American Rescue Plan but, alas, we haven’t developed that technology.

We really do have demand-driven inflation, created by Democrats’ policies

There’s a lot of pat commentary from liberals rejecting the idea that US inflation has been driven by US fiscal policy — inflation is high all over the world, we’re told, so how can we blame Biden or Democrats for high prices? But when people talk about high inflation “worldwide,” what they really mean is high inflation in Europe:

Europe, as you may have read in the news, is facing a severe energy crisis due to the Ukraine War. The war has driven up energy prices globally, but it has done so especially acutely in Europe, which had relied heavily on Russia for oil and natural gas. Before the war, inflation was running hotter here than there. Now, it’s higher there than here, but it’s high for different reasons — Europe’s inflation is almost entirely driven by supply shocks, while ours comes from a combination of supply-side and demand-side factors.

If you take a truly worldwide view like Sen. Sanders suggests you might, and look at other rich countries that aren’t as directly exposed to Russian energy markets as Europe is, you’ll find inflation rates that range from modestly lower to much lower than ours. Inflation has run at 6.8% over the last year in Australia, 7.2% in New Zealand, 3.0% in Japan, 5.6% in South Korea, 2.8% in Taiwan, and 6.9% in Canada.1

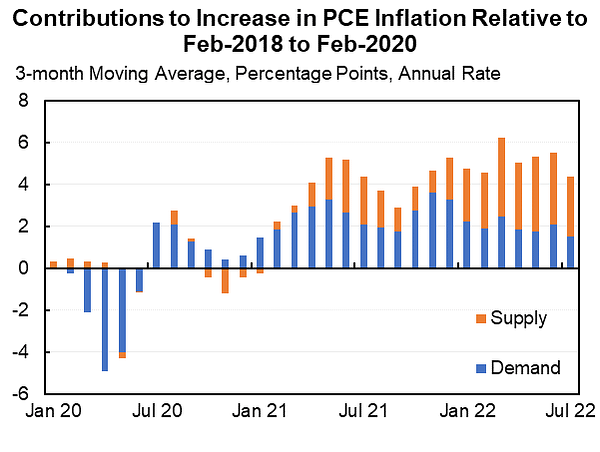

Jason Furman highlights research from Adam Shapiro at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco that seeks to break out the supply- and demand-driven aspects of US inflation. Roughly, the idea is that if a product or service is rising in price while the quantity of the product or service falls, that looks like supply-driven inflation, as when gasoline prices rise because of reduced availability of gasoline. But if price and quantity are rising simultaneously, that looks like inflation coming from the demand side — supply is actually expanding, but demand is running even hotter than supply.

And what it looks like when you decompose those factors is that demand drivers are adding about 2 percentage points to US inflation in recent months — without them, instead of being in the ballpark of 8% inflation, we’d be around 6%.

Of course, 6% is still too high, and it would still be a large political problem, but it wouldn’t be as large of a political problem and elections are won on the margins.

As you can see in that chart, supply factors have been an even bigger driver of excess inflation than demand factors. Much of that supply-driven inflation was due to the huge spike in energy prices from the war, which is unfortunate luck for Biden. Democrats are right when they point out that more oil and gas land leases today won’t produce more oil products and lower prices tomorrow, but if Biden had started from day one of his administration with a posture of seeking to promote North American energy production — proceeding with Keystone XL, auctioning oil and gas leases at a normal pace, and generally signaling (as the administration is now coming around to doing) that capital investments in US oil production will be rewarded rather than stranded — we might have greater North American production today and a less extreme spike in energy prices. Plus, if Biden had been trying to promote North American energy production all along, he’d have more credibility now when he talks about the issue: Republicans have long been advocates of drilling, pipelines and refining, while Democrats have waffled, and that hurts when voters are concerned about energy prices.

So that’s all very annoying — a bunch of mistakes made early last year that are proving very politically and economically costly now.2 And what's additionally annoying is that an argument about mistakes made in the past often doesn't tell you enough about what to do in the future.

Looking forward to the next Congress

While Republicans have a mostly coherent critique about how Democrats fueled inflation — ARP was too big, IRA doesn’t do very much to reduce deficits, student debt relief is inflationary — they have not been clear at all about what they’d do going forward to push inflation down. They can’t claw back the ARP funds any more effectively than Biden can. (They have also attacked Biden for the most clearly disinflationary component of his fiscal agenda: tax increases.) On energy, Democrats have made a real and laudable shift toward abundance and deregulation, embodied in the permitting reform agenda pushed by Sen. Joe Manchin. Republicans, who have long wanted permitting reform, killed Manchin’s proposal for political reasons.

If Republicans win and pursue fiscal austerity, it’s fairly likely that voters won’t like their approach. They’ll have to look to things like entitlement cuts, since they also don’t have a time machine for un-passing the ARP and they won’t want to raise taxes. But there’s one key way this time is different from 2011 to 2013. Liberals are scarred by the budget fights of that era and the unwarranted austerity demanded by Republicans that held back the recovery at a time when the economy was sluggish. This time around, the composition of the austerity could be undesirable or unjust, and the process of imposing it could be damagingly chaotic, but at least the macroeconomic effects of the austerity itself are likely to be salutary — mostly leading to lower inflation rather than lower output.

The main lesson for Democrats is they need to find a way not to end up in this position in 2024. Liberals can complain all they want about voters blaming Biden for high prices, but they now seem to get that elections are generally about the economy, and that voters aren’t happy with an economy with sharply rising prices and falling real incomes even if jobs are plentiful.

The main job now is ensuring that the economic situation that prevails in 2024 is more conducive to getting people to vote Democratic. Policies they enact today can’t do a lot to affect gasoline prices or inflation before Americans vote in two weeks. But they can matter over the next two years. So if Republicans win, Biden should look for ways to work with them to expand energy production — again, a longstanding Republican priority — and should fixate on containing inflation (including through fiscal austerity) rather than fueling it with gimmicks like student debt relief.

Very seriously,

Josh

Nice.

There is, by the way, a parallel story on border security — rash moves in the winter of 2021 to rapidly unwind the Trump administration’s border policies intensified a wave of migrants who have rushed to our southern border while they believed it would be possible to enter and remain in the US. Of course it was not effective to send Vice President Harris to Guatemala to tell them not to come. Nor have the administration’s muddling policies at the border — which do keep many migrants out, often relying on Trump-era mechanisms which the administration gradually came to realize it could not afford to jettison — been effective at countering the impression of openness made by that initial move. The best option would be to go back and un-make the mistake, but that’s not possible, and the administration does not have great tools at its disposal this year to clean up the mess it made last year.

Josh provides a good self-reflection on policies that are ideologically driven without consideration of the basic reality of the impacts in a large energy driven economy. The elite progressive position on rapid decarbonization at all cost without sufficient consideration of energy economics or energy security leads to declining standard of living for the poor and middle class. It is not surprising that the non-elite class is pushing back.

It’s hard for me to understand how it was that there was no push back (at least that I’m aware of) within the Biden administration. How could anyone not understand that trying to reduce fuel consumption so quickly was going to backfire? It impacts just about everything in our economy, and now that truckers are paying at least twice as much for diesel, that is showing up in our supply chains and what we pay for groceries, and pretty much everything else these days.

Great article.