Don't Sweat the Falling Stock Market

It's the least of our concerns — and it's falling for a good reason

Dear readers,

I hope you had a good weekend. We had a special Monday issue of Very Serious yesterday, only for paying subscribers, in which I shared my thoughts about the business plan Elon Musk has been showing to potential investors in Twitter (implausibly aggressive on user growth) and about how Chuck Schumer’s leadership decisions continue to make me want to stick my finger through my eyeball (extensively). If you missed that, subscribe now and you can check it out.

But today, I want to talk about stocks, which haven’t been doing so hot lately.

One term you may hear Federal Reserve officials throw around from time to time is “financial conditions.” This term refers roughly to how easy it is for participants in the economy to get their hands on capital. Financial conditions are “loose” when interest rates are low, stock prices are high, and credit spreads are low —that is, private borrowers don’t pay that much more to borrow than the US government does. When those indicators turn around, financial conditions are tightening.

Right now, we want financial conditions to tighten. Inflation is too high, and all kinds of market participants need to cool it a little bit so the upward pressure on prices will abate. And for all of this year, the interest rate component of financial conditions has been tightening a lot, led by a Federal Reserve that has been raising interest rates and signaling its intention to raise rates quite a bit more.

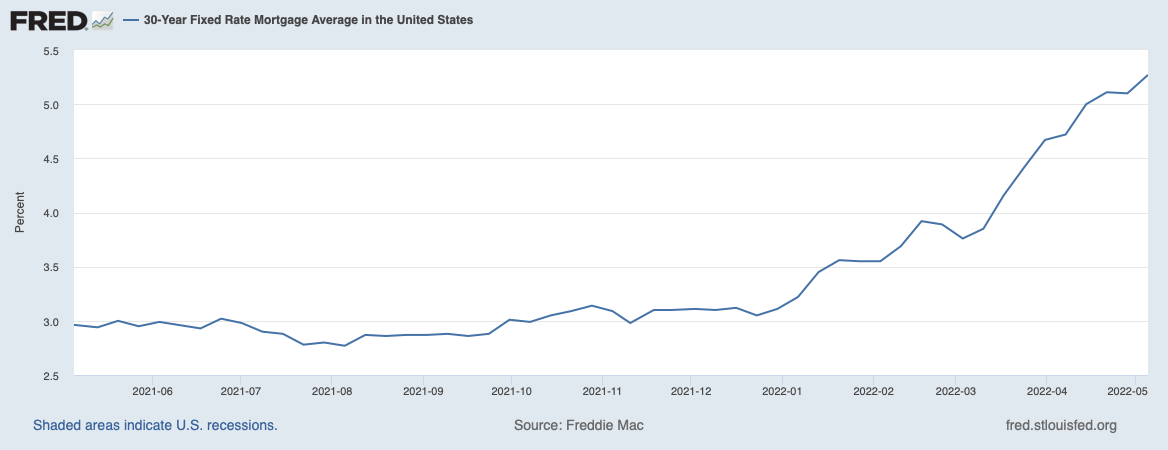

If you’ve been trying to buy a home, it’s likely you’ve noticed this tightening of financial conditions. Here’s the average rate on a 30-year fixed rate mortgage, as reported weekly by Freddie Mac. At the end of last year, it was 3.11%. Last week, it was 5.27%.

To put that in more concrete terms, the monthly payment on a newly originated $400,000 30-year fixed-rate mortgage has gone up by about 30% in a bit more than four months, from $1,710 to $2,214.1

In theory, this upward march of mortgage rates should already be helping to push inflation down. The higher monthly cost to borrow will discourage homebuyers from bidding up prices as much as they might have previously. Those who do buy may not be so aggressive in their other areas of consumption. And the same effect applies in all sorts of other areas of credit: higher interest rates for credit cards and auto loans discourage consumer spending, while higher corporate bond yields make companies more cautious about borrowing to invest and expand.

An odd thing is that this shift in financial conditions was a bit late to show up in the stock market.

Higher interest rates, all else equal, should mean lower stock prices. That’s because a stock, like a bond, is a claim on future cash flows — though instead of a fixed schedule of principal and interest payments, a share of stock provides a right to a proportional share of future profits and returns of equity capital. And so when bonds become a better deal for investors (by paying a higher yield) stocks should do the same, in order to maintain their attractiveness as an investment relative to bonds. The way stocks make that adjustment is by falling in price: If the price is lower, then the expected annual return relative to the price you paid is higher.

Of course, it’s never the case that all else is equal. If the economic outlook is awesome and the expected trend for future corporate profits is improving a lot, then that’s a force that should push stock prices up. Bond prices don’t benefit from this like stock prices do — when a company does great, stockholders make a lot more money, while bondholders still just get the fixed payments they were promised. And often, interest rates are going up because some underlying positive thing is happening in the economy — such as the strong demand and robust pace of economic growth we’re currently experiencing, which has been one of the drivers of the inflation we’re having to deal with.

Still, interest rates have gone up so much that it makes sense for stocks to have fallen, even if investors retain a positive attitude for profits and growth. And I think that’s how you can think of the stock market correction we’ve seen so far — it’s consistent with the ideas that (1) economic growth is slowing down and (2) higher interest rates call for lower price-to-earnings ratios, not with the idea that the economy is going to hell.

A cooling of stock prices should also hopefully help cool off inflation: The negative “wealth effect” from lower brokerage account balances should discourage some consumption (and some bidding wars over houses), and the higher cost of capital for corporations that want to issue new equity should be a moderating force on corporate investment. Basically, we’re seeing what’s supposed to happen when the Fed does what it’s been doing lately.

Of course, there’s other trouble out there. As Jason Furman described on the podcast last week, economic fundamentals are worse today than they were in February because of negative real events in Ukraine and China that are disrupting supplies of fuel, agricultural products, and other goods. And turning an inflation spike into a soft landing is always a challenge for a central bank. The Fed needs to cool the economy but not freeze it, and while the current pace of rate hikes seems obviously appropriate, it will be hard for the Fed to figure out next year whether it’s done enough.

So while there’s a lot to worry about in the economy, I wouldn’t put this stock correction on the list. Stock prices were going to need to fall for the overall inflation-fighting program to work, and that’s what they’ve been doing.

Very seriously,

Josh

And because short-term interest rates have been rising along with long-term ones, you can’t even save that much on interest in the near term by getting an adjustable-rate mortgage. According to NerdWallet, the currently prevailing interest rate on a 7-year adjustable-rate mortgage is less than half a percentage point lower than on a 30-year fixed.

One question here - I know that theoretically rising interest rates should make people less likely to take on auto/home loans or to buy on credit, but are people that rational? I've talked to exactly zero people who've said "with these higher interest rates, I think I'll be deferring my decision to buy a home for a bit". This lack of rationality seems like an even bigger risk in the credit card space.

Or is that why this kind of economic cooling behavior by the government often causes a recession? Because people won't change their behavior until the environment is truly scary?

I'm not sure I agree here - look at the movement on these rates vs. equities

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=PfTR

Market estimates of inflation are as high as ever (5-year, 5-year is a good tell, because it leaves out "transitory"), equities have been collapsing, and real rates are spiking.

Real rates spiking is interesting because it either means real growth estimates are increasing (doubtful given equities collapsing), or probability of default is increasing. The latter is obviously not great...