How Not To Talk To The Public About Monkeypox

A case study in hiding the ball, public health official-style

Dear readers,

Happy Wednesday! You may have seen some FBI-related news this week — if you’re interested in the Mar-a-Lago raid, including some inferences about the status of the investigations into and around Donald Trump, I recommend you check out the newest episode of Serious Trouble with me and Ken White. (Remember: Very Serious paid subscribers can email mayo@joshbarro.com for a 50% discount on Serious Trouble, which will get you access to the full length episode.)

We also talk about one thing Trump could do if the purpose of the raid really was bizarrely picayune — he could release the warrant, which the FBI agents were required to leave at Mar-a-Lago when they executed the search. The warrant doesn’t contain all the information about why they think there’s evidence of a crime at Mar-a-Lago, but it does say which specific statutes they’re investigating Trump under. So far, he’s keeping that under wraps.

But now: monkeypox, and the public health officials who keep gaslighting us. A reader, Everett, referred me to a recent interview with a public health official in Portland, Oregon, about monkeypox that really hits all the wrong notes about how to talk to the public about this outbreak:

I would like to share a piece of a recent interview I heard on OPB (Our NPR affiliate). The guest is a senior adviser with the Oregon Health Authority, the state agency that was also in charge of most policy decisions for Covid-19. Here is the exchange between Jenn Chávez (OPB host) and Dr. Tim Menza (OHA adviser) that left me a bit puzzled.

Yeah, this interview was really bad. I want to talk about the manner in which it is bad, because while it’s just one interview with one public health official in one state, Dr. Menza does four things that are emblematic of how public health has repeatedly failed us in recent years:

He fails to include developing knowledge about an ongoing outbreak in his public communication about how this outbreak is happening.

He lets woke ideology get in the way of clear communication.

He withholds information because he doesn’t trust the public to use it in the way he would like them to.

He unnecessarily alarms the broad public about a disease with fairly specific risk factors, while failing to effectively highlight those factors for those most at risk.

As you know from reading this newsletter, there are several ways that monkeypox can spread, but in this outbreak it largely is spreading though sexual contact between men. So, you would think, when the OPB host asked “what are the best ways for people to reduce their risk of contracting the virus?” Menza might have at least mentioned sex. Unfortunately, he did not. He found time to discuss the risks associated with a handful of other activities — being in an office, learning in a classroom, going to a bar or a club, massaging someone with monkeypox sores, etc. — but couldn’t quite bring himself to say “sex.”

Here’s his interminable answer to that simple question:

We can kind of try to put activities to specific risk levels. Things that I would say are unlikely to transmit hMPXV are things like taking public transportation, going out to eat, going to the grocery store, going to have coffee with friends, being in an office with your coworkers and learning in a classroom. Those things are all low-risk activities. Hanging out outside at a bar or a club or a cafe, totally low risk activities.

Being in more crowded spaces where there’s less clothing and more skin-to-skin contact, like a bar or club perhaps, that’s where that skin-to-skin contact comes into play. We’ve been trying to message to folks to just consider the amount of skin-to-skin contact you might expect in a situation or a place that you might be or an event that you might be attending.

And then the things that then move up in scale are things that include more prolonged skin-to-skin contact. Like perhaps massaging an area with skin that is affected by hMPXV, or hugging in contact with skin that is affected by hMPXV. Or perhaps cuddling. The other thing is we know that when we talk about respiratory secretions we think about saliva too. So things like kissing or sharing a toothbrush might be a little bit higher risk.

And then the things that have the most risk is when there’s that really direct prolonged skin-to-skin contact with the sores, the scabs or the fluids of the rash.

Imagine you were a person who knew nothing about monkeypox. Would hearing that answer help you understand what monkeypox risks you have and what you can do to address them? Not really. If you’re not a man who has sex with men, you might come away inordinately concerned that you’ll catch monkeypox from being in a crowd at a concert. If you are a man who has sex with men, you won’t be informed of your particular risk from sexual exposure — which is a problem, because CDC data as of late July showed that 99% of US monkeypox cases had been in men, and 94% of those men with data provided to the CDC reported “sexual or close intimate contact” with another man within the 3 weeks prior to the start of symptoms.

And even if you — still a gay man, in this hypothetical — read between the lines of Menza’s weirdly prudish musing about what constitutes “prolonged skin-to-skin contact” (“perhaps massaging… or hugging… or perhaps cuddling…”) and infer that sex might be one of the major risks here, you’re still liable to be improperly reassured by Menza’s overemphasis on the importance of contact with sores and scabs.

Most people, I think, instinctually avoid extended contact with other people’s sores and scabs without having to be told to do that by a public health professional.1 But if you’re led to believe that contact with sores and scabs is essential to spreading monkeypox, then you might infer that it’s low-risk to have sex with someone who has clear skin. And until very recently, the CDC was reassuring the public that it’s impossible to spread monkeypox without symptoms. But as the NYC Department of Health has been correctly warning gay men, we don’t know if that’s true — and the manner in which this outbreak has propagated itself would frankly make more sense if there is a significant degree of non-symptomatic spread.

Menza did eventually get around to talking about gay men, sort of, when prompted by his interviewer (who, of course, went directly to the issue of “stigma” before anyone devoted any time to the question of whether gay men need any particular information about risk reduction):

Chávez: Right now my understanding is that many of the cases in Oregon have been found in cisgender men who have sex with men. And I’m wondering how you are approaching public health messaging around this — resisting stigmatization and shame and blame while also still targeting those most at risk right now with resources.

Menza: It’s quite the challenge. What we’ve been trying to do as best as we can is stick with what we know. In the United States, we know that people assigned male at birth who have sex with men and people assigned female at birth, including at least one pregnant person, have been affected by hMPXV in Oregon. We know that cisgender men and nonbinary people are affected by hMPXV. While most identify as gay or queer and report close contact with people assigned male at birth, we have cases that also identify as straight and bisexual and report close contact with people assigned female at birth. (emphasis added)

It is simple enough to say that monkeypox is spreading especially among men who have sex with men. If you also say that there is elevated risk for trans and nonbinary people who have sex with men, you’ve covered the whole universe of elevated sexual risk for monkeypox in a clear and understandable way. Instead, Menza starts by talking about, for some reason, “people assigned male at birth who have sex with men and people assigned female at birth” — that is, to a first approximation, gay men plus women, which is not anywhere close to an accurate description of the high-risk group.

It is unacceptable, if you have Dr. Menza’s job, to speak in woke word salads like this. Menza is speaking on a broadcast news program. It is his job to communicate in clear terms to the broad public. And few members of the public describe themselves as “assigned male at birth” or even think of their sex as something that was “assigned.” This is woke jargon, and it’s unsuitable for a news interview.

Menza also insists on calling the disease hMPXV — later in the interview, there’s an extended discussion of why he doesn’t like the term “monkeypox” — but again, clarity. People have likely heard of monkeypox. They have not heard of hMPXV. Even if you feel the name is unfortunate, it’s the name people know. Why are you confusing the public in pursuit of some political objective about disease names?

He goes on:

That being said, it is a challenge because just like you pointed out, we want to use our data to prioritize and drive our outbreak response. So from our perspective, Oregon Health Authority really needs to provide the people most affected including cisgender men who have sex with men, nonbinary folks and folks who identify as gay and bisexual with support care, vaccines and other prevention tools, especially when resources require thoughtful prioritization. (emphasis added)

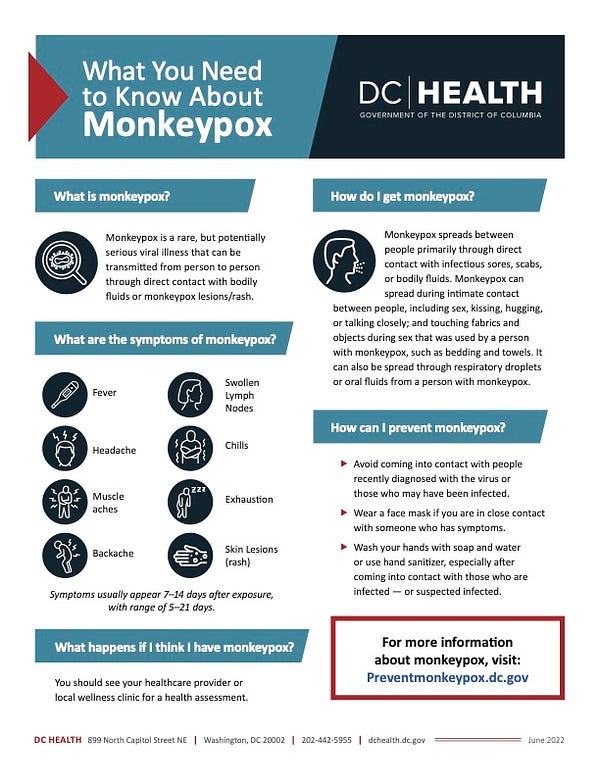

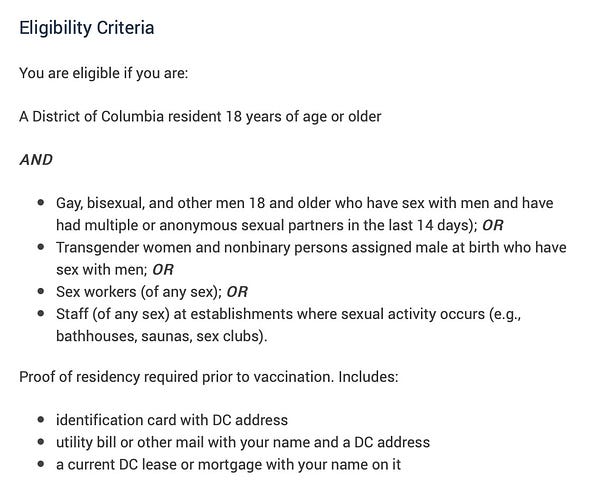

What “thoughtful prioritization” means is that, when it comes time to allocate scarce monkeypox vaccine, the same public health officials who hem and haw and obfuscate about “anyone can get monkeypox” suddenly become really clear that they’re looking for men with multiple or anonymous male sex partners. For example, compare the DC Department of Health’s monkeypox “one-sheet” with the webpage where DC Health says who can get a monkeypox vaccine — it’s night and day.

Unfortunately, back on OPB, Dr. Menza continued on:

At the same time, we know that anyone can be affected by hMPXV. And so we want to provide a level of awareness to those who may not be affected to quite the degree that gay and queer men who have sex with men are affected. And so at times we do feel caught between how we communicate to the general public and then how we have another channel of communication to folks most affected by hMPXV. And our strategy has been this is to really use our community partners to do a lot of the community engagement and communication to folks who are most affected by hMPXV. Partly because … the messaging is best delivered by folks and organizations who know the communities best. And so our task has been trying to partner as much as possible to listen to those communities and to hear how best we can support [them]. (emphasis added)

This makes me angriest of all.

He’s being explicit: There’s one message for the general public, and another message that they’re trying to deliver only to gay men. They rely on “community partners” to deliver that secret message. Well, first of all, what about gay men who listen to Oregon Public Broadcasting? I promise you there are gays listening to public radio. And if they hear this interview, they’re going to come away less informed and less equipped to avoid monkeypox than they ought to be.

Another problem with this secret-message strategy is that information about who’s in a high-risk group isn’t relevant only to people in the high-risk group. It’s relevant to people not in the group, because it helps them figure out their risk isn’t high. And this goes to the part of the monkeypox messaging nonsense that isn’t political correctness — it’s neurotic public health officials being inveterately incapable of telling anyone their risk is low due to demographics.

But the biggest problem with this messaging strategy is simply that it is dishonest.

Menza knows something — that this outbreak is happening almost entirely through gay sex — but in this interview, he’s hiding the ball about that because he doesn’t trust the broad public with that information. He’s concerned that knowledge of this fact will cause people to stigmatize gay men.

I first of all think it is crazy — if you want to avoid stigmatizing gay men — to induce straight people to be unnecessarily afraid of acquiring, through casual contact, a disease that is spreading mostly among gay men through sex. But I would also note that we have just gone through a multi-year process in which the public esteem for the public health apparatus has dimmed considerably. People have noticed that public health statements were not always on the level, and that makes them less inclined to trust those statements. (Remember the CDC telling people in March 2020 not to wear masks? And then not acknowledging airborne COVID spread until October 2020? Remember thousands of ‘experts’ signing that June 2020 letter saying it was suddenly okay to go out in public so long as you were protesting for the right political causes?)

And public health officials, instead of swallowing their pride and trying to regain public trust, have been incredibly arrogant, continuing to view themselves as the judges of what information the public can and can’t be trusted with, as they try to supply and withhold that information in the way they think will best shape public behavior toward their own ideological ends.

Frankly, I feel a great deal of despair about this situation. We do need public health experts. Their work, when done well, is important. But the field is full of leftist weirdos who let ideology get in the way of facts and who can’t help themselves from putting their thumbs on the scale to promote their preferred ideological outcomes. As a result, many of them are incapable of doing their jobs properly, especially when the job description entails behaving in a manner that might engender the trust of the broad public. And I don’t know what to do about that.

Speaking of trust in officials, FDA Commissioner Robert Califf has made a pretty “whoa, if true” announcement about monkeypox vaccines: That we’ve found a way to inoculate people with just one-fifth the normal vaccine dose amount. The FDA says injecting the JYNNEOS vaccine intradermally (that is, within the skin) induces a much stronger antibody response than the usual subcutaneous injection, which in turn makes it possible to greatly shrink the vaccine dose, so we can get 5 or 6 shots out of what is supposed to be a one-dose vial.

Or at least, the FDA thinks it will work that way.

I am genuinely unsure what to make of this decision, and relevant experts are divided on it. It does seem clear that the smaller intradermal injection does just as well at inducing the production of antibodies as the larger subcutaneous injection. What’s less clear is whether that means it’s similarly equivalent for producing immunity — immune responses are complex and, as many of us learned during COVID, don’t always simply correspond to antibody titer levels. It’s also unclear how quickly local health departments can scale the new vaccine strategy, which will be more complicated to administer and require retraining the professionals who provide the injections.

The problem is we don’t have any available options that are known to be better than the one the FDA is advancing, since we don’t have enough vaccine to immunize the relevant population through the usual administration method, and we likely won’t until well into 2023.

As I’ve written before, several large health departments are currently dealing with the vaccine shortage by delaying the second dose of the two-dose vaccine regimen. As with the switch to an intradermal injection, it’s currently unknown exactly how much that impacts effectiveness. Another option is to use an older smallpox vaccine that we have in much more ample supply, ACAM2000, but that vaccine has an unappealing side-effect profile and also (unlike JYNNEOS) consists of a replicating live virus that can be spread through contact with the injection site.

In these difficult circumstances, I am pleased to see the FDA getting creative in a situation where creativity was needed. But we wouldn’t be in this position if the FDA and other agencies had made better decisions months and years ago. Hopefully, the outcry over this shortage will be the wake-up call policymakers need to ensure there is adequate vaccine stockpiled for the risk of a smallpox outbreak, when the stakes would be far, far higher than they are now — and just as important for straight people as for everybody else.

I’ll be back tomorrow with some thoughts on inflation.

Very seriously,

Josh

I’m really sorry that we have to talk about this.

Josh's recent posts about monkeypox have me thinking about the dangers of being overly obsessed with "inclusion." A sizable and influential faction on the left seems to have decided that the most important thing in the world is to make sure that no one feels weird or stigmatized. That's fine in principle. We should want to be nice people.

But sometimes it really matters that someone is unusual! When I was little, there was a boy in my school who wore a bracelet to show that he was allergic to bees. It said something like, "Serious bee allergy, EpiPen in pocket." Having him wear that made his parents and the school feel okay about letting him play outside during recess. But kids being kids, he'd sometimes get made fun of for his "girly" bracelet. And yet no one, no one, suggested that every kid in school be made to wear a bee bracelet so he wouldn't feel weird. If everyone had a bee bracelet, that would entirely defeat the purpose of the kid with the actual allergy having one.

I feel like so much official messaging about monkeypox has been, "Everyone needs to wear a bee bracelet."

And that's not the only thing where people have been doing this. Talk about pronouns has taken this really weird shift lately where certain people are now advocating that EVERYONE introduce their pronouns. (I actually got berated by an activist for not including pronouns in my email signature at work. I so badly wanted to reply, "Um, this is an email. The only pronouns I'm using are 'I' and 'you.'")

But...doesn't that remove the whole point of introducing your pronouns? Like, wasn't the original purpose supposed to be a social nicety, a discreet way of signaling that you're worried about being misgendered and you want to save anyone the embarrassment of doing it?

If everyone's doing it, that signal is lost. There's no way to tell the people who really care about being misgendered from the people who are only stating their pronouns because they don't want to be perceived as a Bad Ally.

It just doesn't make sense to me. You can be sensitive and courteous and still realize that not all language can be "inclusive." Sometimes it can't be, not if the goal is to communicate necessary information to the audience that needs it.

With apologies to the Barro-tariat commenting community, and I'm not sure this is exactly the right place to put this, but maybe it is useful for it to be said--

I am fairly young (in that coveted 18-49). As far as I can remember, I have never missed an election, and I have never voted for a Republican (each on the merits, not a party-line vote). I have a PhD--while I respect the trades greatly, I am bigly checking all sorts of socio-political-educational-economic boxes. Very bigger and very large than many people are saying, with tears in their eyes, very large and strong voters.

What the *fuck* does "cis" mean vis-a-vis "straight"?

All manner of personal regret to anyone who I may have offended--this is not my intent, and yet, I do ask sincerely. I can't be *that* unique, can I?