Jay Powell Brings the Pain

The rate hikes will continue until well after the data improves. The question is: How can Biden make rate hikes less necessary?

Dear readers,

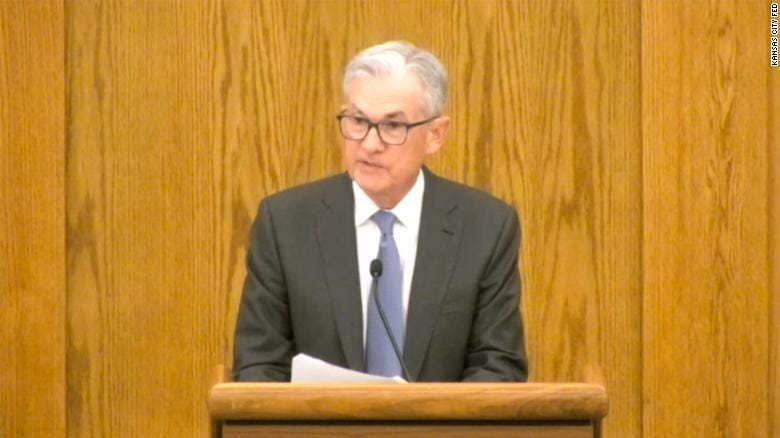

Fed Chair Jay Powell spoke only for eight minutes Friday at the Federal Reserve’s annual research conference in Jackson Hole. And the message he delivered was clear: We are not close to done with the interest rate hikes. Here are some excerpts:

At past Jackson Hole conferences, I have discussed broad topics such as the ever-changing structure of the economy and the challenges of conducting monetary policy under high uncertainty. Today, my remarks will be shorter, my focus narrower, and my message more direct…

Reducing inflation is likely to require a sustained period of below-trend growth. Moreover, there will very likely be some softening of labor market conditions. While higher interest rates, slower growth, and softer labor market conditions will bring down inflation, they will also bring some pain to households and businesses. These are the unfortunate costs of reducing inflation. But a failure to restore price stability would mean far greater pain…

July's increase in the target range was the second 75 basis point increase in as many meetings, and I said then that another unusually large increase could be appropriate at our next meeting… At some point, as the stance of monetary policy tightens further, it likely will become appropriate to slow the pace of increases. [Josh adds: the subtext here from the “at some point” is that while the rate increases will get smaller eventually, September is still likely to be another 75-basis-point increase.]

[W]e must keep at it until the job is done. History shows that the employment costs of bringing down inflation are likely to increase with delay, as high inflation becomes more entrenched in wage and price setting. The successful Volcker disinflation in the early 1980s followed multiple failed attempts to lower inflation over the previous 15 years. A lengthy period of very restrictive monetary policy was ultimately needed to stem the high inflation and start the process of getting inflation down to the low and stable levels that were the norm until the spring of last year. Our aim is to avoid that outcome by acting with resolve now.

The stock market fell sharply after he made the comments, which is likely an intended consequence. Alan Blinder, a former vice-chairman of the Federal Reserve, described succinctly to Brian Cheung of Yahoo! Finance what Chair Powell’s likely objective was here:

I’ve heard this from several people around the Fed in general — not from Powell himself — that they’re bothered by the idea that you see in the markets a lot: That by early next year, they’re going to be cutting rates already. And I don’t think anybody on the Federal Reserve thinks that’s very likely.

The Federal Reserve directly controls short-term interest rates, but it only influences longer-term interest rates and other financial conditions, such as stock prices, that affect the level of desire that businesses and individuals have to invest and consume. And a problem for the Fed’s efforts to tame inflation by cooling the economy is that the markets have not been fully buying the Fed’s insistence that it’s going to keep tightening quite aggressively in the future — because market participants haven’t believed that short-term interest rates will be as high in the medium-term future as the Fed claims they will be, longer-term interest rates haven’t gone up as much as the Fed would like.

So Powell basically went out and said the same things he and other bank officials have been saying in recent months, but louder and simpler and with more of a subtext of irritation, and the market reacted accordingly: bond yields moved up and stock prices plunged. Amusingly, CNBC quotes one fund manager replying almost directly to the complaint voiced by Blinder about wanting market participants to stop expecting rate cuts to start up again in early 2023:

“We do believe the Fed,” said Zach Hill, head of portfolio management at Horizon Investments. “We believe what they say that rates are going to be higher for longer and we’ve seen some repricing of the cuts in 2023. We think there’s more to go on that front and it’s likely to continue to fuel equity volatility from here.”

The Federal Open Market Committee will next meet to set interest rates on September 20 and 21. One thing I’d take away from Powell’s remarks is that, absent some truly shocking economic data, there will be another 0.75% rate increase. And when he does a press conference after announcing that rate decision, I’d like to hear him respond to some big fiscal policy news that has happened since the committee last met in late July.

One of the strongest criticisms of the Fed’s response to the COVID crisis is that, when Democrats unexpectedly won control of both houses of Congress and enacted a much larger fiscal stimulus than had been expected for early 2021, the Fed did not adjust its posture commensurately to reduce monetary stimulus, and as a result, the economy became overstimulated. (Hindsight is 20/20, and I did not spot this error at the time, either.) And since July, we’ve gotten three significant pieces of news that should further affect the Fed’s view on how much of a headwind or a tailwind their monetary policy is getting from fiscal policy:

President Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act, which will somewhat reduce budget deficits, though not starting until 2027, and which contains policies to encourage energy production and regulate prescription drug prices, which should have microeconomic effects that reduce inflation,

Biden announced he will seek to cancel hundreds of billions of dollars of student loan debt, approximately offsetting the expected deficit reduction from the IRA, and

Biden also announced that the moratorium on student loan repayments and interest, which amounted to about $60 billion per year of fiscal stimulus, will end at the end of this year.

I’d like to know how this combination of fiscal actions affect the Fed’s view of the need for fiscal tightening. Partly, the answer to this question depends on a tedious baseline issue: Did the Fed already expect the student loan interest moratorium to end soon? My guess is that they did and that these fiscal actions combine to be approximately a wash: taken together, they don’t affect the inflation picture much at all.

But that’s too bad because the IRA is, after all, called the Inflation Reduction Act, and one of its benefits should be that it causes inflation expectations to fall and therefore reduces the need for the Fed to cut inflation through rate hikes, which, as Powell notes, impose pain through “softer labor market conditions” — i.e., more unemployment. This is why, as I noted yesterday, I think it’s so weird to shrug off the likelihood that student debt forgiveness will require the Fed to go substantially higher than it would otherwise need to in this rate hiking cycle.

But as a political matter, debt forgiveness is water under the bridge — maybe the courts will throw it out, but it’s too late for Biden to decide he’s made a mistake and reverse his inflationary policy. Instead, the White House should look for other non-monetary levers to reduce inflation. At the top of my list is that they should fight to get Joe Manchin’s permitting reform side-deal to the IRA done — this will encourage infrastructure investment, make it possible for the IRA’s budgeted energy investments to actually get built, and press down on inflation by making energy cheaper and more abundant. They should lift the Trump-era tariffs I’ve been complaining about all year. And as Matt Yglesias writes this week, they should review the policy approaches — particularly around automation, staffing levels and trade protectionism — that Democrats backed as “job creating” in a time of slack labor markets. These policies simply inhibit growth and promote inflation at a time when the labor market is tight and economy is close to capacity.

Powell has made clear the Fed isn’t going to stop until it knows it has inflation licked. So it’s up to the White House and Congress how much they want to work with the Fed on the inflation-fighting project and how much they want to work against it — because that will help determine how high rates actually have to go, and the level of attendant economic pain we will feel.

Cocktail hour: It’s Friday evening, and I thought you might like to hear what I’m drinking today.

I’m a member of the bar club at Napa Valley Distillery1, and as a member they send me a few bottles of odd things once a quarter. I have some blueberry vodka from them that I haven't really known what to do with. So, tonight I made a very refreshing gin-blueberry-lemon sour for a warm summer evening.

1⅓ oz Roku gin

⅔ oz Napa Valley Distillery blueberry flavored neutral brandy2

1 oz lemon juice

½ oz NVD “Grand California” orange liqueur3

½ oz NVD strawberry citrus syrup

Combine all ingredients in a shaker with ice, shake vigorously, and strain into a rocks glass with ice. Or, if you have received them as a thoughtful gift from a houseguest (or bought them on eBay) you can use vintage 1960s Continental Airlines first class cocktail coupes, like so:

That’s all for today. I’ll be back with you next week.

Very seriously,

Josh

Neither I nor Very Serious Media received any consideration or even free product from any of the distillers discussed here. Sad!

NVD describes these products as “neutral brandy” because, being in Napa, they make their spirits from a grape base. But for all intents and purposes, this is vodka.

While this is my favorite orange liqueur, there is one I like nearly as much that’s less expensive and widely available in liquor stores around the country: Pierre Ferrand dry curaçao, which (like the NVD Grand California) has much stronger orange aroma than Grand Marnier or Cointreau.

Thank you for this very straightforward analysis. This is why I subscribe . Very Seriously, worth every dime.

Is that a grill I see in the background? Gasp.