Now It's Republicans' Turn to Try for Abundance

Our country needs a more productive economy and especially a more productive public sector. Can either party deliver that?

Dear readers,

Fifth Avenue is New York’s most important shopping street. The sidewalks are often bursting at the seams with pedestrians, especially on the mile-long stretch of Fifth Avenue between Central Park and Bryant Park. Last month, New York Mayor Eric Adams announced that New York City will soon commence work on that important segment: narrowing the roadway from five lanes to three to make way for an expansive sidewalk and attractive plantings — all intended to provide a more pleasant pedestrian experience, draw shoppers, and increase sales tax revenue.

The project will entail an “initial investment” of $152 million, with an estimated total budget of $350 million.1 In other countries, $350 million would buy you a mile of subway line. In New York City, it’s the cost of a glorified paving project — albeit a very attractive paving project, with a couple hundred trees and 20,000 square feet of planters spread out over 20 blocks, but a paving project nonetheless.

In the last couple of years, there has been a fashion among centrist Democrats for pursuing an agenda of “abundance,” which principally means building more things for less money. This push is a reaction to sticker-shock from projects like the one on Fifth Avenue, and more broadly to decades of American failure to build transportation and energy infrastructure and housing stock in adequate quantities at reasonable costs. It’s also a reaction to changing macroeconomic conditions in the last few years — higher interest rates and higher inflation make it more important to increase productivity and pursue capital projects in a cost-effective manner.

Despite occasional protests to the contrary from its advocates, the abundance agenda is necessarily deregulatory. It means getting the government out of private sector builders’ way and, just as importantly, out of its own way. Zoning laws need to be loosened. Building codes made more flexible. Opportunities for environmental litigation restricted. Government agencies freed to make contracting choices based on cost and expertise, instead of being hamstrung by rules intended to promote other social goals like bolstering union employment or “buying American.” Especially in a time of high inflation, Democrats need to stop being the party that makes things more expensive and instead be the party that makes them cheaper — by means other than subsidizing those things with scarce taxpayer dollars.

The Democratic Party has led on deregulation in the past. As has been widely noted in Jimmy Carter’s obituaries, he signed laws to deregulate the airline, rail freight, trucking, natural gas and telecommunications industries — laws all passed by a Congress controlled by Democrats. And what brought Democrats around to deregulation in the late 1970s was a political-economic environment similar to our current one: Politicians in any place on the political spectrum needed to find ways to fight inflation, and one low-pain way to fight inflation was to remove regulations that made airfares and freight rates higher than they needed to be. I keep seeing people declare the death of neoliberalism, but I expect a resurgence — the same political incentives that led Jimmy Carter and Ted Kennedy to become deregulators in the 1970s apply today, and they will apply more urgently if interest rates remain elevated for years to come.

That said, deregulation cuts against Democrats’ natural instincts, and the party has had difficulty pursuing abundance in recent years. Ezra Klein has termed this problem “everything bagel liberalism”: when Democrats set out to fix a problem, they feel the need to include some goodies for every interest group in their coalition. So, you set out to build semiconductor infrastructure (or whatever) but you include environmental goals and union employment goals and “equity” mandates, and you end up adding a lot of cost and a lot of delay. Sometimes the big problem with these programs is that they cost too much money — we end up building “affordable” housing that costs a million dollars per unit, for example. But other times, the problem is that the government doesn’t even manage to spend the money it’s supposed to spend, because it’s too tied up in paperwork and meetings and lawsuits to get shovels in the ground. This has been a recurring theme with Biden-era infrastructure programs — for example, the 2021 infrastructure bill allocated $42 billion for rural broadband expansion, but it hasn’t actually produced any rural broadband expansion yet, in large part because the Biden administration added a zillion strings to the funding that have made it difficult to come up with plans about how states will actually spend the money — climate goals, union set-asides, price regulation, “equity.” Maybe, in 2025, states will actually start taking the money and laying fiber. But since that’s still a theoretical proposition, is it any wonder that rural voters did not reward Democrats for the investment in rural broadband that hasn’t actually happened?

A few weeks ago, when I appeared on the Fifth Column podcast, the hosts asked me if there was anything I was looking forward to about the next Trump administration. And there is: I’m looking forward to Republicans taking their crack at abundance and seeing if they can do better than Democrats. Slashing red tape and getting the government out of the way is at least supposed to be a Republican strong suit. Maybe they’ll do some of it? As Politico noted in a September story on the non-existent rural broadband rollout:

As the months go by, there is also another clock ticking loudly on the program’s broader policy goals. If voters return former President Donald Trump to office in November, Republicans will have wide latitude to rewrite its rules — possibly wiping out Democratic requirements for accessibility, union participation and climate impact, and almost certainly dialing back the affordability rules that have caused so much friction in Virginia.

I sure as hell hope they do! A broadband program should be about broadband, and if Republicans come in and strip out all the coalition-pleasing, cost-adding, delay-causing detritus that Democrats crammed into the program, that will be great and I will be pleased.

At some abstract level, Trump’s economic team seems to understand that they will need to promote abundance. Inflation remains somewhat elevated, the federal budget deficit is excessive, and Trump wants to cut taxes more without cutting Social Security or Medicare. If he pursues a deficit-increasing fiscal policy like he did in his first term, Trump will create upward pressure on interest rates, and if he succeeds at bullying the Fed into keeping rates lower than it should, inflation will ensue. Faster economic growth would be very helpful to Trump officials trying to deal with that interlocking set of problems, and incoming Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent likes to talk about a “3-3-3” plan: grow the economy at 3% a year, cut the deficit to 3% of GDP, and increase domestic oil production by 3 million barrels a day.

Of course, it’s easy to throw out numbers; it’s a lot harder to shave the federal budget deficit from over 6% of GDP to 3% while cutting taxes, or to grow the economy by 3% a year while removing millions of unauthorized immigrants from the labor force. I expect the administration to take a friendlier approach toward the fossil fuel industry, but I’m still skeptical they will succeed at growing U.S. oil production by more than 20% from what are already record levels. And there are reasons to wonder about a new Trump administration’s ability to deliver even the deregulatory aspect of an economic growth agenda. Last time he was president, Trump started out inclined toward housing deregulation but ended up promoting a pro-regulatory agenda that branded his support for restrictive zoning as “saving our suburbs.” He has aligned himself with the longshoremen’s union to oppose port automation. Trade protection and reduced immigration, two of his signature policies, are ways to de-liberalize the economy and dampen the growth outlook. While tax cuts can promote growth — especially cuts in marginal tax rates — they will put upward pressure on interest rates (and therefore downward pressure on growth) if they are financed with more government borrowing. And some of his tax-cutting ideas (like “no tax on tips”) grow the deficit while doing little or nothing to promote growth.2

We have started to see Republicans’ internal fight over abundance play out in the form of Elon Musk’s feud with nationalist conservatives over the H1-B visa program. Musk argues that highly skilled immigrants (like himself) promote innovation and growth and that we should have more of them. Many of Trump’s other supporters simply don’t want immigrants here, even if that means less abundance. The anti-immigration interests are Republicans’ version of Democrats’ labor unions and environmental groups, coming to the table and demanding that their preferences be put ahead of abundance.

So far, on the H1-B visa issue, Trump has indicated he’s siding with Musk. I will be interested to see how consistently Trump makes the pro-abundance choice in these intra-party disputes — especially if, a year into his administration, inflation and mortgage rates have continued to trend upward, making a politics of abundance all the more urgent. But I hope he chooses abundance more often than Democrats managed to under Biden.

Very seriously,

Josh

Not including the cost of relocating utilities, which we’ll learn more about once they rip up the street.

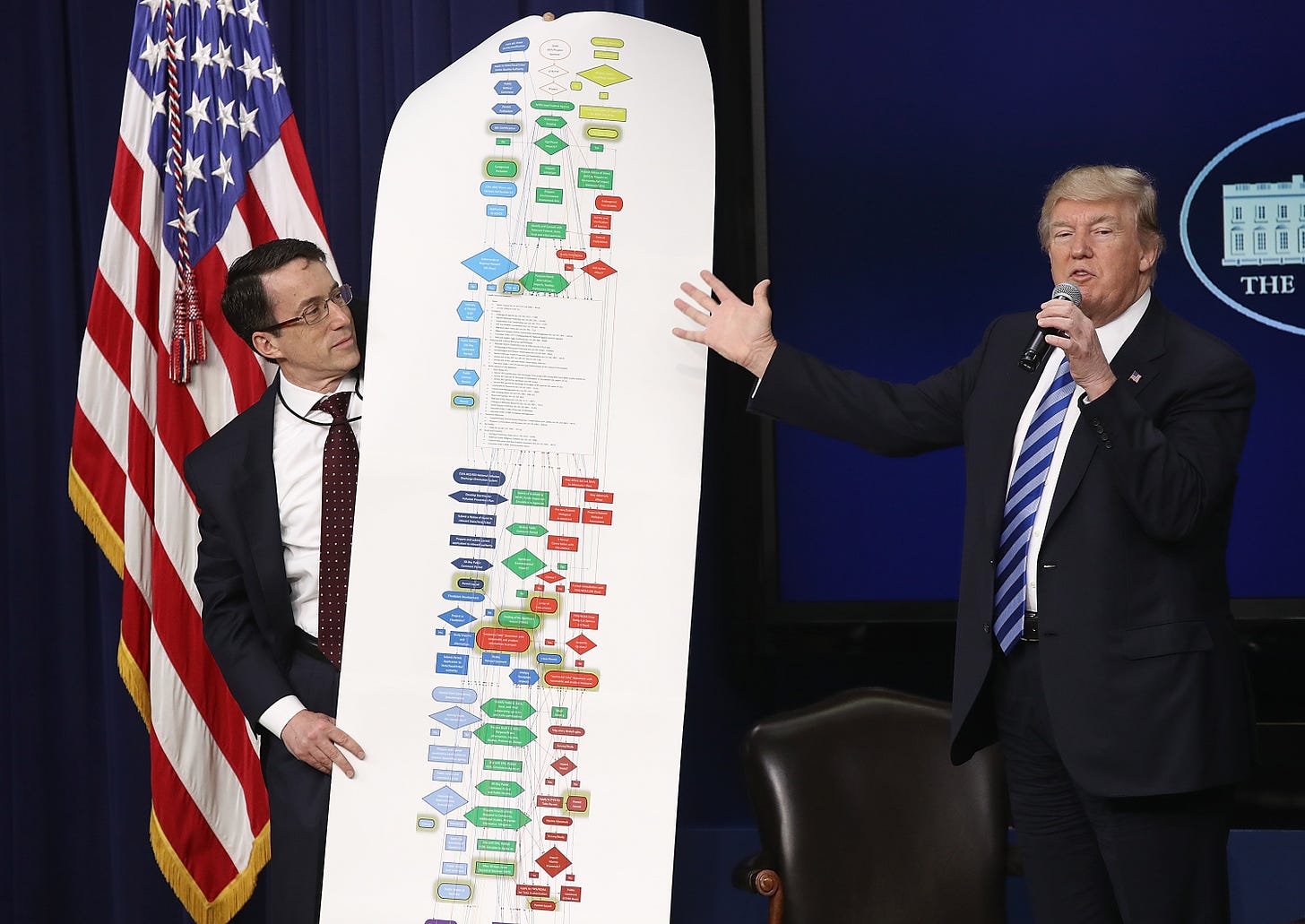

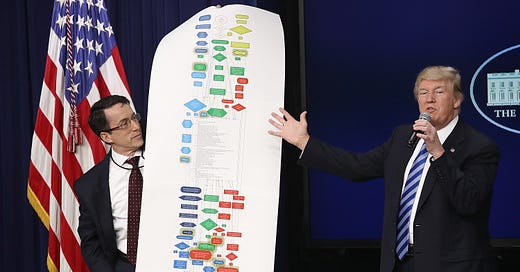

There’s also the matter of DOGE, the Elon Musk-Vivek Ramaswamy initiative that is supposed to make the federal government more efficient. I am all for efficiency, and on some issues, Musk is a voice pushing in the right direction on efficiency, like when he urges President Trump to support and expand high-skill immigration to the United States. But the DOGE effort has thus far been dilettantish, with Ramaswamy offering ideas that betray his shallow knowledge of how our government works, such as proposing to save “hundreds of billions of dollars a year” by ending appropriations whose authorizing acts have expired — apparently not realizing he had proposed to shutter the VA hospital system, the FAA, and America’s embassies and consulates abroad. I do not have high hopes that DOGE will produce big ideas that make our government a lot more efficient; on the other hand, given its leaders’ dilettantishness about the legislative process, I do not have high fears that they will succeed in convincing a near-evenly divided House of Representatives to pass draconian cuts to social programs.

Great article. Democrats treat the quote ‘if you try to please everyone you’ll please no one’ as a mission statement to rather than a warning. Trump’s Musk/VC wing of supporters and the nativist/nationalist wing seem to be at odds with each other and if Trump tries to please everyone on his side I feel he’ll have the same results as the Democrats have been getting.

As I've noted on MattY substack, as best we can tell from various polls, GOP voters are less in favor of upzoning and deregulating housing sector than Democratic voters. The loudest left voices against building more housing are often in NYC or SF (see Aaron Peskin) and as a result get disproportionate news coverage. But it's not actually strictly true that Dem voters (and maybe more important Dem politicians) are more likely to be against upzoning and building more housing**.

I bring all this up because, in theory I agree with your post. But basically have to note that the second part of your post is probably more relevant here; there's a lot to suggest to me that GOP pursuing an "abundance agenda" is a bit of a pipe dream. Call me a partisan Dem if you'd like, but the deregulatory agenda of GOP has for quite a while been mostly about doing favors for their elite donors*.

*If an abundance agenda does actually come to fruition via the GOP, the mechanism seems like it will be the courts. Ending Chevron deference should probably be long term good for an abundance agenda narrowly speaking. I'm still very worried about this court ruling given that it seems like it's going to lead stuff like the Fifth Circuit declaring that since deference doesn't have to be given agencies like the FDA, they can rule that mifepristone is a great danger to the public because it will cause societal breakdown by giving women too much control (I'm not really joking that based on past behavior I can see Fifth Circuit ruling this way based on this reasoning). But it should also in theory lead to much shorter delays getting projects built due to delays from environmental review. Again, this seems like a "baby with the bathwater" situation in that seems like a mechanism for getting rid of all environmental regulation. But I don't think I'm crazy in thinking this could lead to possibly more not less solar panels getting built.

** I should note by opinions on a lot of topics like this is colored by living in Long Island; quite possibly the national epicenter of right wing NIMBY.