This Week in the Mayonnaise Clinic: Was Roe v. Wade a Stolen Base? What About Overturning It?

Not exactly. But abortion politics is about to change in a way Republicans aren't prepared for.

Dear readers,

Welcome back to the Mayonnaise Clinic! Let’s get to your mail.

Andrew asks:

I like your stolen base politics analogy (though also consider it evidence you don’t watch baseball much, given that actual stolen bases are most certainly earned). I’m interested in whether you think conservatives are “stealing a base” by overturning Roe precedent via their (ill-gotten?) court majority? Did liberals steal the original base with the Roe/Casey rulings themselves? Is tit-for-tat base stealing more kosher than first-strike base stealing?

First of all, if you want to take issue with the metaphorical idea that a stolen base is unearned, take it up with whoever decided to call the baseball play a “stolen base.” It’s right in the name!

This is going to sound strange, but I don’t think my “stolen base” metaphor maps well onto constitutional rulings like Roe or the forthcoming one that is likely in Dobbs. What I was talking about in that article was a set of ill-conceived political strategies for forcing undesired policies on an unwilling public. One of the strategies I complained about is attempted disqualification (just screaming “Trump” and “January 6” about your Republican opponent); another was insistence on expert deference (empowering a bureaucracy to impose undesired policies and saying we simply must do what the experts say).

The thing about Roe is that, as a strategy, it was not ill-conceived. It worked. While more voters describe themselves as pro-choice than pro-life, it imposed a set of abortion policies on the whole country that are significantly to the left of the median voter’s preferences. And because the Supreme Court is not accountable to the elected branches of government (unlike the CDC), voters did not have direct recourse over Roe — even if they had wanted recourse, which most didn’t, in the sense that Roe has long been popular, polling better than pro-choice identification and much better than the full suite of policies implied by Roe.

So maybe that means Roe was a successfully stolen base, but when Terry McAuliffe tried to beat Glenn Youngkin by running against Donald Trump, he got picked off. Is my baseball metaphor better now?

As for Dobbs, I don’t think can constitute a stolen base because it doesn’t impose a particular policy anywhere — it will be state governments that impose abortion policies. A lot of state governments will soon impose broad abortion bans — quite a few have “trigger laws” that would automatically ban abortion if Roe is overturned — and those laws will be unpopular in most places. This is a longstanding policy goal for Republicans, so this doesn’t make them the dog that caught the car. But I don’t think they’ve quite prepared for the political implications of the win they’re likely about to get.

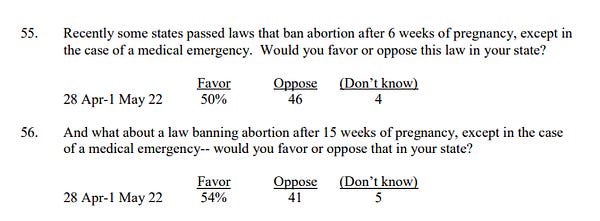

For example, Republican operative Logan Dobson has a tweet this morning that says something that is true enough: Policies that limit abortion to a period fairly early within pregnancy tend to poll well.

I wouldn’t take to the bank the idea that a 6-week ban, specifically, is popular. That’s a narrow margin in one poll, and G. Elliott Morris points to polling for The Economist and says “the median opinion is that abortion should be banned except for emergencies sometime just after the end of the first trimester.” The distinction is very important — much more important than the difference between, say, a 15- or 20-week ban, because of the large fraction of abortions that occur within the first trimester but after the sixth week. Nonetheless, the broader point is right: most voters don’t favor broadly available abortion for as long into pregnancy as Roe and Casey have required it.

But also: so what? In a post-Roe world, we’re not going to be arguing about laws that ban abortion at 6 or 15 or 20 weeks. We’ll be arguing about laws that ban abortion at zero weeks, and that’s going to be an electorally tough position for Republicans to defend.

In Texas, for example, a complete ban on abortion is significantly underwater in polling — 54% opposed and 42% in favor, according to an April poll from YouGov and the University of Texas.

Texas Democrats will surely seek to capitalize on that if and when abortion is entirely prohibited in that near-purple state. But what will their alternative proposal be? If they seek to broadly legalize abortion only in the first trimester — the public policy of a lot of other advanced countries, including many in Europe — that will be a more popular position, and they might even win an election on it and be able to implement it. But if they stick to the incredibly rigid script that has become dominant in Democratic politics, where abortion should be legal and even subsidized up to the moment of birth — see Nan Whaley, Democratic nominee for governor of Ohio, unable to name a single restriction on abortion she favors — then they’ll just be another extreme counterpoint to the extreme Republicans.

I sometimes see takes about Roe that don’t make a lot of sense, suggesting that we wouldn’t even have much of an abortion debate if courts had stayed out of the matter and let voters grapple through and resolve it themselves. These takes were often rehashed to say Obergefell was going to lock in a permanent gay marriage divide, something we don’t see at all in the polling.

But I do think one thing Roe did was lock the center out of discussions of abortion. Republicans have sought intermediate restrictions not because they favored them substantively but as a strategy to get toward total prohibition, while Democrats have grown increasingly hostile toward any kind of restriction. Polling makes clear that huge swathes of the country are in between.

Maybe the voters in those swathes go unheard because their positions are morally incoherent and not well developed, or because their in-between stance simply reflects a desire not to have to think too much about abortion. I wrote a few weeks ago about how muddled public opinion on abortion reflects a sense that pregnant women and their unborn children have valid and conflicting moral interests, which the law must consider and balance without being able to vindicate both at all times. I can’t take that observation and turn it into a convincing moral argument about why abortion would be acceptable at 9 weeks but not 16 weeks.

But since these voters in the middle are showing themselves to be cross-pressured between two instincts on the abortion issue, it’s important that they hear arguments and proposals that operate within that frame of that cross-pressure — arguments that emphasize how total or near-total bans on abortion will impair the moral interests of women those voters have shown themselves to place weight on. But these voters’ frame is not compatible with the idea that abortion is a purely private matter between a woman and a doctor: the cross-pressure evident in public opinion reflects that most American adults see a fetus as a morally relevant entity with interests that the state should acknowledge and, in some instances, protect through restrictions on abortion.

Democrats should be prepared to argue within that frame not just because they lack other options but because, most of the time, voters thinking within it will come out their way. If you took the great public opinion muddle on abortion and turned its midpoint into the bundle of policies most closely resembling it, you’d end up with one where the vast majority of abortions performed under the Roe/Casey regime would remain legal, because the unusual cases Republicans feel most comfortable arguing about are just that: unusual.

Republicans are going to take the new legal powers the Supreme Court is likely to give them and take policy quite far away from where the median voter is because they sincerely and deeply care about the issue. They’re prepared to incur political costs for doing that. But for Democrats to actually inflict those costs on Republicans — and win elections in the places where they’ll need to in order to change abortion policy — Democrats will need to meet the public where it is.

Travis asks:

While it seems generally settled that ARP (American Rescue Plan) spending has contributed to inflation, is it just the spent portion that is considered inflationary? Or is even the unspent portion considered to be a contributing factor?

Most of the ARP funds have already been spent by the government, but there are two aspects of lingering ARP funds that continue to drive inflation.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Very Serious to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.