Where Democracy Was on the Ballot, It Won

Voters took the counsel to reject some — but not all — Republicans.

Dear readers,

I’ll start with this: My rejection of the utility of the “democracy is on the ballot” argument was too flippant, in part because I took the argument to be more sweeping than it actually was — or at least, more sweeping than voters took it to be.

I wrote, days before the election (emphasis added):

The message is that there is only one party contesting this election that is committed to democracy — the Democrats — and therefore only one real choice available. If voters reject Democrats’ agenda or their record on issues including inflation, crime, and immigration (or abortion, for that matter), they have no recourse at the ballot box — they simply must vote for Democrats anyway, at least until such time as the Republican Party is run by the likes of Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger.

But as you look at the sweep of the results across the country — with the popular vote for the House swinging several points toward Republicans from 2020, and yet Democrats tending to win where it counted most, and the most “MAGA” Republican Senate candidates underperforming the Republicans downballot from them — what you see is that voters made fine distinctions among Republicans. A decisive bloc of swing voters took the view that a Republican Party of Kari Lake and Tudor Dixon and Don Bolduc was too extreme, too autocratic, and too weird to earn their votes — but that a Republican Party of Brian Kemp or Mike DeWine or, yes, Ron DeSantis was sufficiently normal to treat this as an ordinary-course election and reject Democrats’ agenda. You can see that voters drew these distinctions within states, too — the reason Republicans are picking up two House seats in Arizona while losing elections for governor and Senate is that a crucial fraction of voters picked Republican House candidates while rejecting Blake Masters and Kari Lake.

Obviously, a message that a specific subset of Republicans should be rejected because they lack sufficient commitment to democracy — a subset that is placed in contrast not just to the isolated likes of Cheney and Kinzinger, but to another very large faction within the party that very often does field candidates and win primaries — is not tantamount to telling voters they have already lost their democracy. This isn’t necessarily the message that Democrats wanted to send — ask a Democrat whether Mitch McConnell has been an enabler of Trump’s autocratic agenda and the answer you’re very likely to get is “yes” — but it’s a message that persuadable voters could plausibly act on, and they did. That voters drew these distinctions among Republicans is a major reason Democrats were able to hold onto the Senate.1

So how does the result change my thinking? Well, I won’t be churlish about future “democracy is on the ballot” rhetoric when Democrats continue to face candidates who unnerve voters by echoing Donald Trump’s conspiracy theories about election theft or saying things like “Republicans will never lose another election in Wisconsin after I’m elected governor.” Enough voters do care about those things to matter for an election’s outcome. But I think it’s also important to note that what this election suggests is that voters applied penalties for those sorts of things to individual Republican candidates, not to the Republican Party as a whole — and as such there are a lot of races where this sort of message will, and did, fall flat.

If Trump is the 2024 presidential nominee, and if he continues to succeed at inflicting terrible nominees upon his party in downballot races, then Democrats can run this playbook again next cycle. But if the next cycle’s nominees are more normal — a prospect that is looking increasingly likely after this election took Trump down a few pegs — then I wouldn’t expect this rhetoric to connect.

Finally, I should note that I still don't fully understand the role abortion played in this election. In some states, it was a clear driver of support for Democrats, especially Michigan, where a ballot measure to protect legal abortion passed soundly and Democrats ran up large margins and regained control of the state legislature. It makes sense that abortion wouldn’t be a potent issue for Democrats in New York, where Lee Zeldin would not have been able to enact anti-abortion legislation as governor. And I’ve seen a lot of people point toward relative caution on abortion restriction as a factor that enabled DeSantis’s re-election landslide — Republicans in Florida banned abortion after 15 weeks of pregnancy and are talking about moving that limit up toward something like 12 weeks in the next legislative session, but have not yet pursued a broad restriction on abortions in the first trimester. Yet there are states where abortion was effectively on the ballot and that didn’t seem to help Democrats at all — Govs. Mike DeWine and Brian Kemp signed strict abortion restrictions into law in Ohio and Georgia, respectively, and it didn’t stop them from cruising to re-election.

It’s clear that the electorate is more pro-choice than pro-life, and that where Democrats can literally put abortion rights on the ballot, they will tend to win. (Ben Jacobs has a very useful piece in Politico Magazine on Families United for Freedom, the group that has run successful pro-choice ballot campaigns around the country.) But I don’t know what this election tells us about abortion as an issue that may continue to weigh on Republicans as candidates for political office.

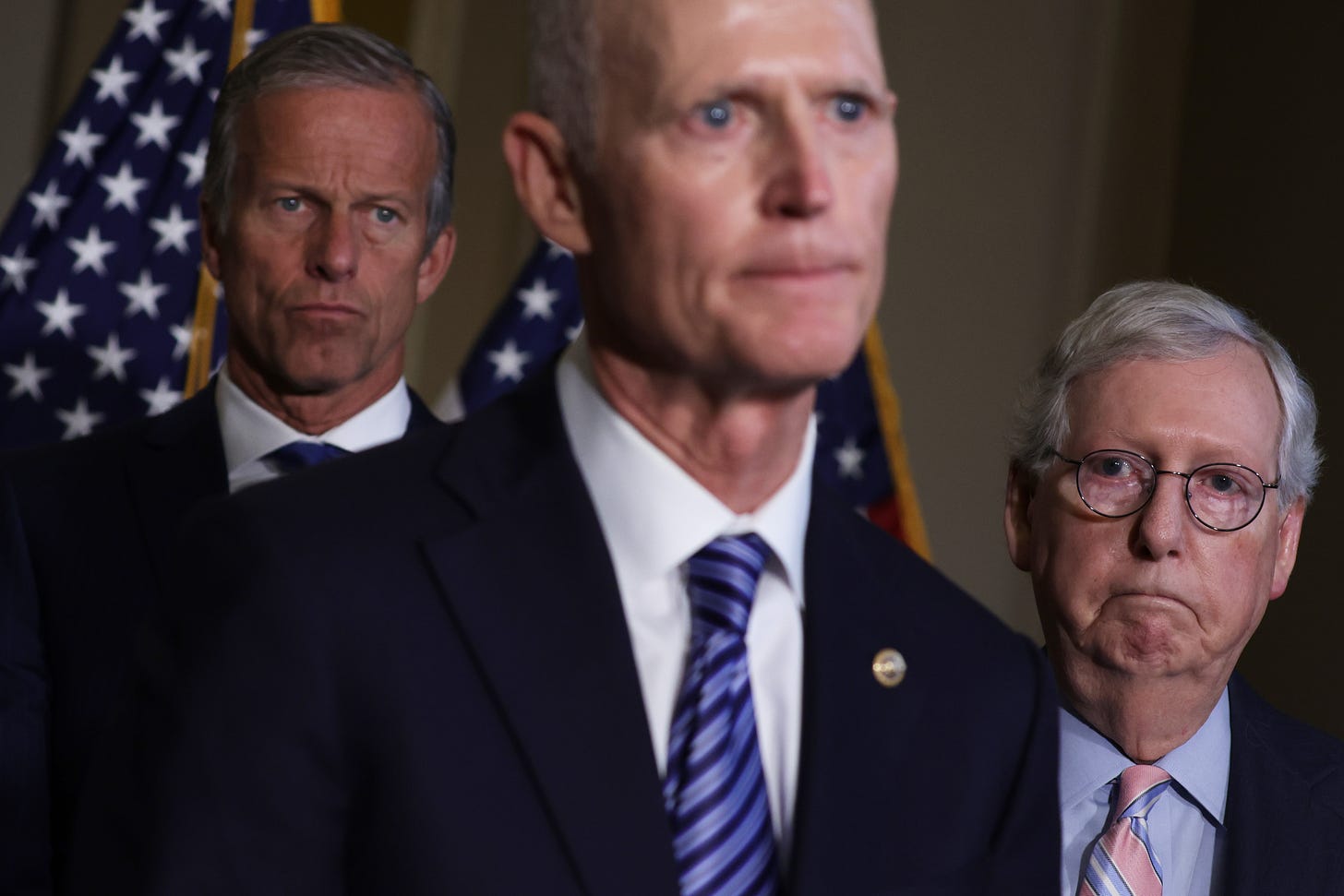

Republicans are reacting somewhat oddly to their underwhelming performance. Rick Scott did a job as chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee that was not just astonishingly poor but obviously self-dealing. He made no effort to promote electable candidates in party primaries — ostensibly, this was a way to respect the will of the voters, but it also conveniently meant Scott never had to get crosswise with Trump and his efforts to hand Senate nominations to his friends and sycophants. He also used the NRSC as a platform to raise his own political profile — including rolling out his own policy agenda for Senate Republicans that became attack fodder for Democrats because it included plans to sunset the Social Security program and raise taxes on tens of millions of middle class families. Basically, Scott burnished his image as conservative fighter and kept himself in Trump’s good graces, and all it cost the GOP was three or four Senate seats.

Scott, naturally, is now running to unseat Mitch McConnell as the Republican leader in the Senate. Scott says “a lot of people have suggested I run.” I assume those people are Democrats. I honestly feel a little bad for McConnell — people on the Trumpy side of the party are attacking him for not throwing more money at races in Arizona and New Hampshire, as though any amount of additional outside spending could have changed the outcome in races that Republicans lost by five and ten points, respectively.

If Republicans find a way to move on from the strategic mistakes they made this cycle instead of doubling down on them — that is, if they reject not McConnell, who didn’t make this mess, but Trump, who did — they’ll probably do it by nominating Ron DeSantis. My take on DeSantis, which I’ll flesh out later this week, is that he’s a beatable candidate with a lot of weaknesses, but that they’re not the weaknesses that Democrats tend to think.

Very seriously,

Josh

It’s important to note that “extreme MAGA candidate” and “candidate quality” have sometimes been discussed interchangeably, but authoritarianism/democracy rejection was only one of the candidate quality problems that Trump saddled Senate Republicans with. Blake Masters musing about privatizing Social Security, Dr. Oz being a dilettante who lives in New Jersey, Herschel Walker being senile and having too many secret children to count — a lot of the candidate quality problems Republicans had were unrelated to democracy being on the ballot.

It continues to baffle me to no end how only the republicans are painted with the goal of authoritarianism.

Both parties would love to be the only party.

Both thinks the other is insane.

I read something recently that that is the one thing they agree on.

I had to chuckle.

It's so close to being true.

If you could just step back and be objective, democrats are as guilty as republicans in their longing for authoritian control.

Interested to hear your thoughts on DeSantis's weaknesses!I